Preventing and healing developmental trauma

Dr Bruce Perry on the therapeutic power of relationships and of pleasurable immersion in predictable sensory rhythms

|

The past two years have been traumatic for many Australian families. In the wake of COVID-19, Australians have experienced job losses, financial insecurity, increased levels of domestic violence (Carrington et al., 2021), home schooling and working-from-home, restrictions on seeing family and friends and a host of other disruptions. On top of that, there have been bushfires and floods for some, drought for others, while none of the typical stressors that affect young families in even the best of times have abated.

In recent Level One Facilitator Training workshops, trainer Paua Mobach has been drawing attention to the work of Dr Bruce Perry, who has specialised in studying the effects of early trauma and in devising an effective approach to treatment for those who have experienced trauma very early in their lives. In this article, we'll take a closer look at Dr Perry's work, and at just how closely this bears on our own activities in Parent-Child Mother Goose. You may find some of the parallels remarkable. Dr Bruce Perry and NMT

Dr Bruce Perry M.D., Ph. D., is an American child and adolescent psychiatrist and neuroscientist whose approach to healing lives affected by early trauma has gained many adherents around the world. In the past he has served as chief of psychiatry at Texas Children's Hospital. He has been a senior fellow at the Berry Street Childhood Institute in Melbourne, and an Adjunct Professor in the School of Allied Health at La Trobe University. He is currently senior fellow of the Child Trauma Academy in Houston. Dr Perry's approach to healing the effects of early trauma is known as the Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics, or NMT. NMT is not a specific therapy, but rather a framework to guide interventionists who are working with people, typically of school age or older, who have suffered early trauma. The first year of life is critical

Of great interest to Dr Perry and his colleagues is the observation that the first year of life appears to be extraordinarily significant in shaping a child's future. Here is Dr Perry speaking about the importance of that first twelve months for what he calls "high risk" children (Early Years Scotland, 2017). The origin of this phenomenon, says Dr Perry, lies in the way our brains operate and develop.

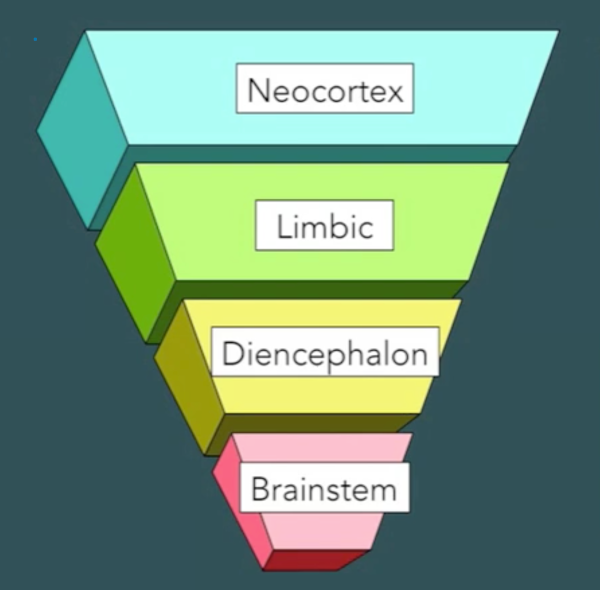

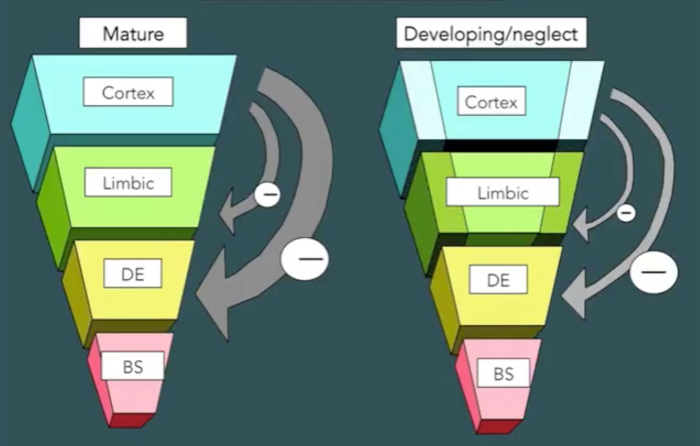

Simplifying matters somewhat, we can say that the human brain consists of four major components, illustrated below (Perry, 2013a). The brainstem accepts input from our senses (sight, hearing, smell/taste and touch) and regulates our breathing, blood pressure, heart rate and body temperature. The diencephalon (and cerebellum) modulate and regulate our sense of arousal and some motor activities. The limbic areas mediate more emotional content, including our feelings of affiliation and attachment. The neocortex mediates complex human functions like thinking, speech and language.

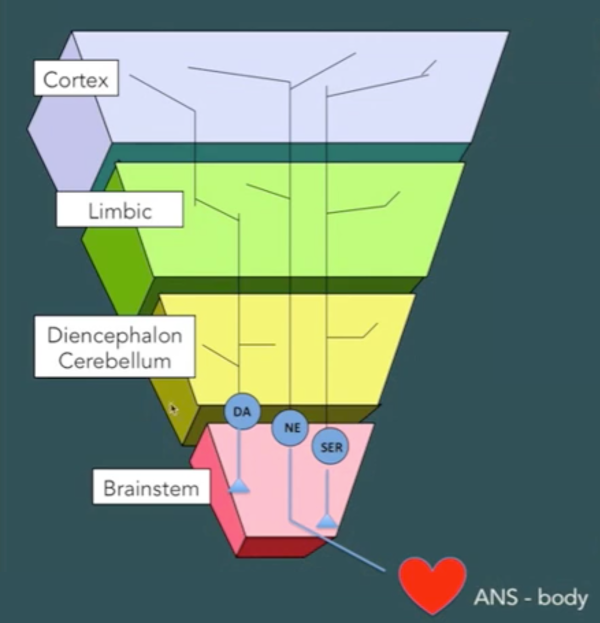

Most of the neurones in each part of the brain communicate only within their own system, but there is some communication between components. Neurons responsive to dopamine (DA), noradrenaline (NA) and serotonin (SER) stimulation extend from the lower reaches of the brain to the upper, and in some cases down into the body, too (Perry, 2013a). When a baby is born, this system only partly developed. The baby's brainstem must be in good working order for the baby to breathe and have a heartbeat, but the further up the hierarchy we go, the less well-developed each component is at the time of birth.

Development of the baby's brain after birth doesn't "just happen all over", so to speak, but occurs in a sequential and hierarchical fashion in response to specific cues in the baby's environment. At an anatomical level, these cues are specific neurotransmitters, cellular adhesion molecules, neurohormones, amino acids and ions, the presence (or absence) of which at certain critical or sensitive periods quite literally shapes the structure and organisation of the baby's developing brain. Perry writes:

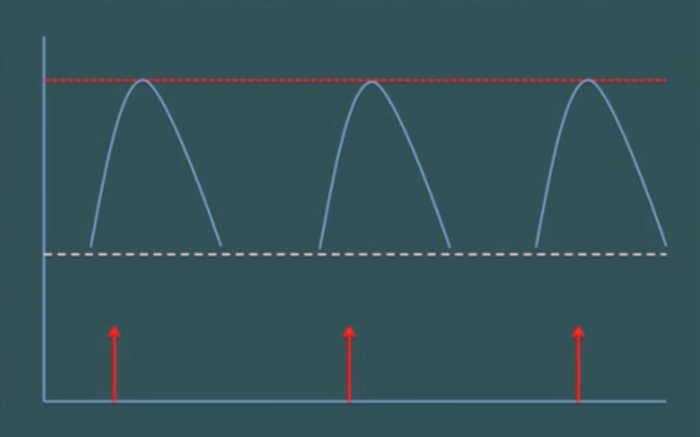

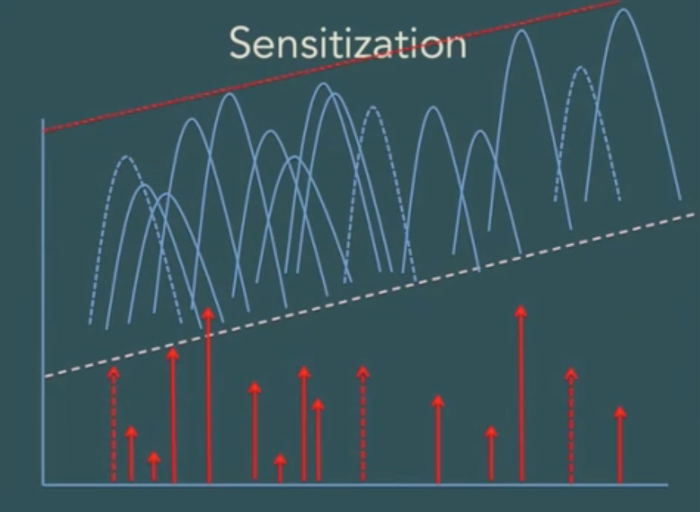

Disruption of experience-dependent neurochemical signals during these periods may lead to major abnormalities or deficits in neurodevelopment - some of which may not be reversible... Disruption of critical cues can result from (1) lack of sensory experience during critical periods or, more commonly (2) atypical or abnormal patterns of neuronal activation due to extremes of experience. (Perry et al., 1995, p. 276) Perry and his co-authors note that: (w)hile deprivations and lack of specific sensory experiences are common in the maltreated child the traumatized child experiences developmental insults related to discrete patterns of overactivation of neurochemical cues. Rather than a deprivation of sensory stimuli, the traumatized child experiences overactivation of important neural systems during sensitive periods of development. (Perry et al., 1995, p. 277) To understand how this "overaction of neurochemical cues" may occur, we need to recall that neurones in our brains communicate with each other by releasing chemicals known as "neurotransmitters" whose presence other neurones detect via specialised receptor cells. The diagram below represents a pattern of stimuli (red arrows) and responses (curved lines) in a neural network where a stimulation (such as a drug or a stress) occurs at spaced out intervals of, say, every couple of weeks (Perry, 2013b). Each response in this case remains proportional to the stimulus.

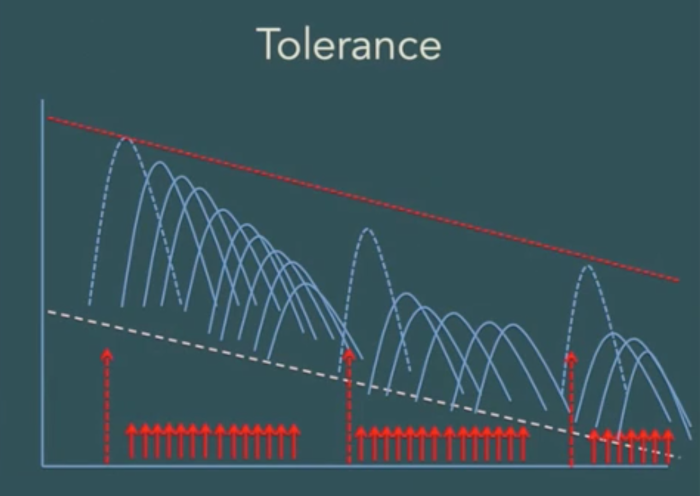

The nature of the response soon changes, however, if we change the way we are stimulating the system. The next diagram illustrates what happens when we provide a pattern of stimulation that is not very strong, for the most part, but is persistent and repetitive (Perry, 2013b). In this situation, the system adapts by making itself less sensitive, and it can become, in fact, almost completely non-responsive. We say that the system has developed "tolerance" to the stimulus. It is this phenomenon that causes drug users to need higher and higher doses of a drug to achieve the same effect.

A quite different phenomenon occurs when the pattern of stimulation is not moderate, continuous and predictable, but is inconsistent in timing and intensity (Perry, 2013b). In this scenario, the neural network actually becomes more sensitive — so much so, in some cases, that a tiny stimulus which previously would have caused only a moderate response now triggers an extreme activation such as a seizure or some other dramatic functional deterioration.

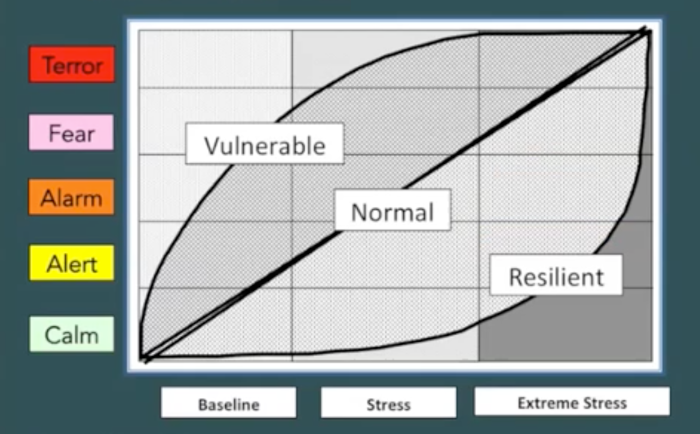

Dr Perry argues that children who grow up in chaos, in unpredictable, threatening environments, exposed to natural or man-made disasters or victimized by abuse and neglect are likely to be highly sensitized to stress, and that this phenomenon explains why. In the absence of any buffering (a matter we will discuss below) this can occur even when the trauma is not a Trauma with a capital T, as it were, but arises because a family is suffering food insecurity, housing insecurity or employment insecurity which are causing a parent to feel tense and anxious, contagiously influencing the young children in the home (Early Years Scotland, 2017). Children whose earliest brain development occurs in such an environment are likely to grow up highly vulnerable, Perry says, responding to any novel (and hence, stress-inducing) situation with a disproportionate level of alarm that shuts down their ability to think and to process the new situation "rationally", at a cortical level (Perry, 2013b). At even a baseline level of stress, where there is no real external threat at all, the brains of these children will tell them that they are under attack, causing them to experience alarm and fear. By contrast, people whose early experience has been more normal are certainly capable of experiencing alarm, fear and terror, but they do so only when the factors generating stress are significantly more intense.

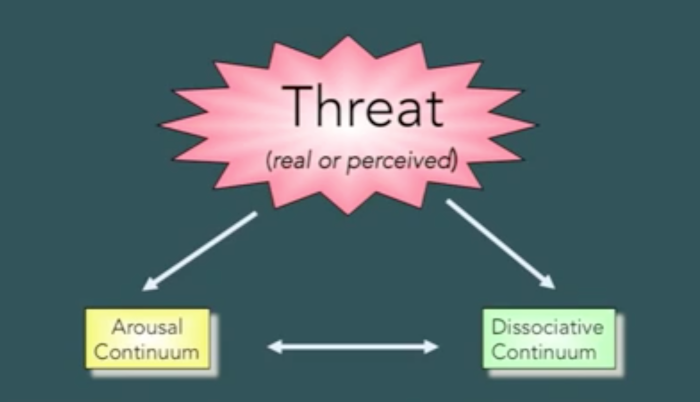

When their sensitised brains become overactive, children (or indeed adults) exposed to trauma in early life are likely to react in one of two ways, broadly speaking (Perry, 2013c). One response is to be become highly aroused, preparing to "fight or flee". The other is to shift into a dissociated state, preparing themselves for surrender by disengaging and "going inside".

Someone on the arousal continuum is likely to appear hypervigilant and impulsive, while someone on the dissociative continuum will appear compliant, numb or avoidant. The younger the person is, Perry says, the more likely they are to dissociate (Perry et al., 1995, p. 282). Sadly, young children in such a state are sometimes mis-characterised as "resilient" because of their seeming non-response to trauma in their lives (Perry et al., 1995, p. 285). The long-term effect of the kind of sensitisation we have described here is profound, causing the very structure of the brain of traumatised infants to develop along a different path, becoming an organ with an inherently weaker capacity to modulate and regulate impulsivity and response to frustration than the brain of a person not traumatised in infancy (Perry, 2013a). Tragically, a person with such a history, readily alarmed by novelty of any kind, hypervigilant and impulsive, or compliant, numb or avoidant, will be operating so much of the time with their cortex effectively shut down that they will be virtually unreachable and unteachable via any appeals couched in language to their cortical functions and reasoning capabilities.

More on NMT

As we mentioned above, much of Dr Perry's recent work has been aimed at helping school-age or older children (and even adults) who have suffered from early trauma through an approach he calls the Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics, or NMT. While NMT as such is not directly applicable to the kind of work we do in Parent-Child Mother Goose, we should perhaps briefly outline the general approach. The key idea is to gain a clear understanding of the person's current state of brain development, and then "build from the bottom up", working first with the traumatised person's "primate brain" (the brainstem, diencephalon and cerebellum), and only later with the person's "limbic brain" and then their cortex (Lyons et al., 2020). NMT does not prescribe specific interventions for use in each phase of the therapy, focussing rather on the general goals and sequence, and giving practitioners the flexibility to pursue these goals by whatever means they think best and are comfortable using. The first phase of treatment (working with the "primate brain") is likely to focus on such ends as regulating the child’s fight/flight/dissociate survival systems, developing co-regulation between child and adult, disarming the child’s survival response in school, and enabling the parent/carer to regulate their own emotions. Once these goals have been attained, the focus should shift to working with the limbic brain, with aims such as building the bonds of attachment, supporting parents to co-regulate and mentalize, and processing traumatic memories. Finally, in the third phase of treatment (working with the cortex), attention will turn to developing the child's sense of identity, making sense of the child's life story, and strengthening reciprocal relationships. Relationships a "buffer" that can ameliorate trauma

In public forums, Dr Perry has spoken often about our deep need for relationships, how relationships reward us and help keep us regulated as we deal with novelty and stress, and about the perverse phenomenon he has noted whereby even the most seemingly "normal" of us today are at risk of falling into "relational poverty". Below we present some excerpts from an Edison Talk Dr Perry delivered at Chicago Ideas Week in 2015 (Chicago Ideas, 2015). Dr Perry has co-authored with Christine Ludy-Dobson a book chapter titled The Role of Healthy Relational Interactions in Buffering the Impact of Childhood Trauma (Ludy-Dobson & Perry, 2010).

Dr Perry and Ludy-Dobson spell out the vital role "healthy relational interactions" play in helping us survive and thrive following trauma: These powerful regulating effects of healthy relational interactions on the individual—mediated by various key neural networks in the brain—are at the core of relationally based protective mechanisms that help us survive and thrive following trauma and loss... Positive relational interactions regulate the brain’s stress response systems and help create positive and healing neuroendocrine and neurophysiological states that promote healing and healthy development both for the normal and the maltreated child... |

The social milieu, then, becomes a major mediator of individual stress response baseline and reactivity; nonverbal signals of safety or threat from members of one’s “clan” modulate one’s stress response. The bottom line is that healthy relational interactions with safe and familiar individuals can buffer and heal trauma-related problems... Although negative early life relational experiences have the ability to shape the child’s developing brain, relationships can also be protective and reparative. (Ludy-Dobson & Perry, 2010)

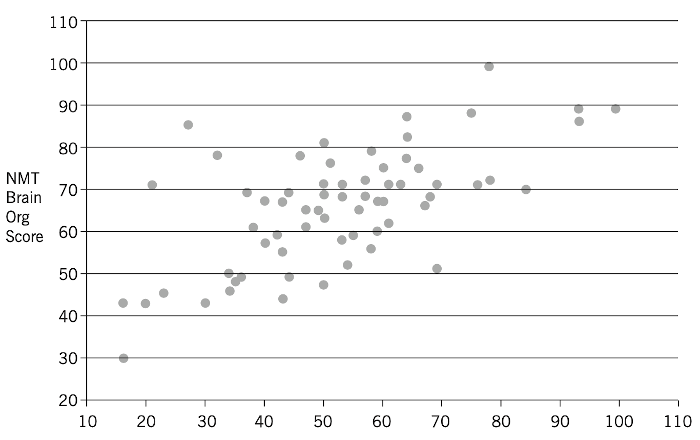

The authors illustrate their point with the following scatter plot (Ludy-Dobson & Perry, 2010, p. 38). The data here are worth unpacking.

The graph is based on research with a group of maltreated children. The x-axis plots a retrospective measure of the presence, quality, and number of relational supports during each child’s development, obtained as part of a clinical assessment of each child. The corresponding value on the y-axis is a measure of the development and functional capabilities of 28 brain-mediated functions, as identified by the NMT Brain Organization Score. Taken as a whole, the scatter plot shows there is a clear relationship between the relational health scores and the overall quality of brain organization and functioning in these children. This suggests that even for children who have been assessed as maltreated, relationships can, indeed, be "protective and reparative". In passing, it's perhaps worth noting that the kind of relational supports Dr Perry and Ludy-Dobson see as "buffers" to the impact of childhood trauma are not therapeutic sessions with trained professionals. Explicitly discounting the idea that "'therapy'—healing— ...(will) take place in the child via episodic, shallow relational interactions with highly educated but poorly nurturing strangers", they write that we tend to "undervalue the powerful therapeutic impact of caring teacher, coach, neighbor, grandparent, and a host of other potential 'cotherapists'" (Ludy-Dobson & Perry, 2010, p. 39). In other words, it is safe, regular connection with familiar individuals — with an extended "clan", so to speak — that is most likely to help "buffer" the effects of early trauma. "Rhythm is regulating"

Also most helpful in organising the dysregulated, sensitised neural networks of a traumatised child, says Dr Perry, is any kind of repetitive, rhythmic somatosensory activity (MacKinnon, 2012). As examples of such activity, Dr Perry lists "music, dance, drumming, grooming a horse, jumping on a trampoline, swinging, massage and a host of other everyday activities." It is the rhythm of these experiences, and their ongoing repetition, that matters particularly, Dr Perry says. The brainstem and diencephalon contain several powerful associations to rhythmic somatosensory activity created in utero and reinforced in early in life. The brain makes associations between patterns of neural activity that co-occur. One of the most powerful sets of associations created in utero is the association between patterned repetitive rhythmic activity from maternal heart rate and all the neural patterns of activity associated with not being hungry, not been thirsty, and feeling ‘safe’. In other words, patterned, repetitive and rhythmic somatosensory activity becomes an evocative cue that elicits a sensation of safety. Rhythm is regulating. (MacKinnon, 2012, p. 214) Particularly powerful, says Dr Perry, is yoking rhythmic sound with rhythmic movement: Essentially your stress response neurobiology is a rhythm. And we're, very, very responsive to patterned, repetitive, rhythmic input that's somato-sensory. And somato means body, so like movement. So rhythmic movement regulates these networks. And rhythmic sounds also regulate these systems. And so when you put together rhythmic sounds of something that somebody's saying with movement, it's a powerful double input to this dysregulated system that you can use patterned, repetitive, rhythmic activity to restore regulatory balance. And it makes people healthy. It allows the part of your brain involved in learning cognitive concepts to open up. (Rhythmic Mind, 2018) Where does Parent-Child Mother Goose fit into this picture?

When social worker Barry Dixon and therapist/storyteller Joan Bodger began running what would later become known as Parent-Child Mother Goose groups in the early 1980s, their work was underpinned by John Bowlby's "attachment theory". This is the idea that a primary loving bond, usually between a mother and child, is critical for little children to develop a sense that they are loved and secure. Bowlby suggested that this positive attachment to the primary caregiver acts as a prototype for all the child's future social relationships and their understanding of how the world will treat them. Bowlby believed the caregiver's choice of words, tone of voice, facial expressions and the way they held or cuddled a young child were critical in shaping that child's development. Dr Perry's ideas appear to be quite consistent with Bowlby's, but extend them in new directions. For example, Dr Perry understands that the absence of a strong relationship can be a very strong risk factor for trauma, but he points also to chaos and inconsistency as causative factors. Attachment theory holds there is a cause-and-effect relationship between early attachment problems and later relationship difficulties without specifying quite how this works, whereas Dr Perry seems to go further, positing a credible biological mechanism by which the damage is done. Furthermore, Dr Perry's model explains not only why the traumatised child is likely to experience relational difficulties later in life, but also provides a neurological explanation as to why the older child or adult is likely to have cognitive and self-regulatory difficulties as well. Dr Perry's model is also richly suggestive when it comes to accounting for the demonstrable effectiveness of the Parent-Child Mother Goose program. Indeed, almost every aspect of Parent-Child Mother Goose principles and practice can be seen to align clearly with some component of Dr Perry's model of how best to minimise and heal early childhood trauma. As we have seen above, Perry has emphasised the "protective and reparative" role of sustained and ongoing "healthy relational interactions with safe and familiar individuals" who can function as a kind of "clan" for the child and its primary caregivers. For the parents, caregivers and young children who join a Parent-Child Mother Goose program and meet together every week for thirty weeks, sitting in a circle on the floor with two trained facilitators to sing songs and chant rhymes and listen to a story, the whole experience does, over time, begin to feel like being part of a "clan". Over time, many participants will find common ground with other group members, sharing tips and resources, and in some cases forming lasting friendships. Through the group, too, participants will often discover other networks of support available in the community for themselves or their children. Furthermore, the whole Parent-Child Mother Goose experience is immersive and pleasurable for both parents and children alike, with strong elements of repetition and rhythm built into the program at every level — within individual songs and rhymes, with their accompanying body movements, but also in the repeating of the regular, predictable structure of each session, which remains essentially the same from week to week, allowing the same songs and rhymes to be sung and chanted from one week to the next, until participants gradually internalise these and are ready to add new material to their repertoire. And because the material is all easily memorised, and pleasurable to perform, it can be taken home and repeated there during the week, as lullabies, as nappy-change songs, or simply as fun, enjoyable activities to share at any time. In none of this is there any recognisable "therapy". There is little explicit appeal to the cortex of parents or caregivers beyond, perhaps, guidance as to how vigorously (or not) one might bounce a baby of a certain age while singing a particular song, what kind of head support might be advisable, and so on. Parent and caregivers are not being asked to "think" so much as to participate. In short, the program is all about getting together with a group of other parents, caregivers and children one gradually gets to know, to enjoy a pleasurable group activity that is powerfully self-regulating both through its immersive "clannishness" and through its thoroughgoing emphasis on patterned, repetitive rhythm in song, rhyme and movement ("up in the air", "down in the hole") — all this performed week after week in a safe setting at a time in the children's lives when their brains are as "plastic" as they are ever going to be. In other words, Parent-Child Mother Goose program offers not so much treatment of the effects of early trauma, as a way of ameliorating, and possibly even of preventing, those effects right at the point where they might otherwise originate. Dr Perry's "6 Rs" when working with traumatised people

Dr Perry recommends that everyone involved in healing traumatised people should follow six principles, which he has dubbed "the six Rs" (Douglas, 2021). Relational

First, all interactions with the traumatised person should be relational, prioritising the need of the traumatised person to feel safe and connected. "Connected" here does not have to mean looking one another in the eye. That kind of interaction can be overwhelming for children (or, indeed, adults) who have difficulty with trust and attachment. Being side-by-side, or even simply completing activities in the same space may well be enough.

In a Parent-Child Mother Goose group, the focus is very much on creating a safe and happy environment for the parents and caregivers, who, for much of a session, sit on the floor with their infants and two facilitators in a circle (that is to say, side-by-side). The facilitators lead the parents and caregivers through a series of activities in which they can relate pleasurably with their infants, enjoying a sense of mutual connection in the moment, while at the same time gaining familiarity with an activity they will be able to repeat and enjoy with their infant later on at home. Relevant

Our interactions should be developmentally relevant. Traumatised children may be developmentally delayed. Carefully observing, and reflecting on, a child’s strengths and weaknesses will help you understand when to challenge a child and stretch their skills.

Parent-Child Mother Goose facilitators are explicitly trained in how to adapt songs and rhymes and their accompanying movement patterns to make them suitable for children with different abilities and preferences and at different stages of development. Part of the reason Parent-Child Mother Goose mandates two, not one, facilitators per group is to ensure that at any given moment, while one facilitator is leading, the other can be free to observe how children and caregivers are responding to a given activity so they can make "mental notes" in order to provide positive feedback, and after the session plan future activities in the light of these observations. Repetition

In our interactions with a traumatised child there should be a high level of repetition. Repetition creates strong neural associations, and helps to mute the highly sensitised stress response we discussed above.

Repetition is the name of the game in Parent-Child Mother Goose. All learning of songs and rhymes occurs purely through aural repetition, week after week. The songs and rhymes we use are strongly repetitive internally (with rhyming lines, and with verses that follow each other with only slight variations), while the overall structure of each session follows the same set pattern, week after week, with only minor variations as new material is introduced slowly over time. Rewarding

The traumatised child should find our interactions pleasurable and rewarding. If a child enjoys an activity, they will want to do it again — and again, and again. Reward leads to repetition, and repetition is great. Find out what the child likes to do best.

Reward, pleasure, delight — these are at the heart of the Parent-Child Mother Goose experience, both for the parents and caregivers and for their children. If children want to do a song or a rhyme again and again, then we want to do that too — and we will, right then and there, in the middle of a session. A typical session also includes time near the end for "special requests", where children or parents can nominate a song or a rhyme they'd like to do again right now. Even a child who cannot speak can often make a gesture that shows the song or rhyme they want repeated. What a delight it must be for that child to know their request has been understood — and acted on. Rhythmic

Our interactions with a traumatised child should include strong rhythmic elements that help to regulate and organise the lower components of the child's brain, potentially helping the child to move into a state where he or she is ready to learn.

Rhythm, repetition — this is core Parent-Child Mother Goose. We often mention that the program uses songs, rhymes and stories, but it is worth emphasising that the performance of all three is typically paired with distinctive physical movements, too, creating the kind of "powerful double input" to the potentially dysregulated system of the child we saw Dr Perry referring to above. For examples of this kind of pairing with distinctive movements, we need think only of the song "Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star", the rhyme "Round and round the garden" or a story like "The Great Big Enormous Turnip" — all Parent-Child Mother Goose staples. Facilitators will find (or create) equivalent patterns of movements to use with other songs, rhymes and stories, too. Respectful

Finally, all our interactions with a traumatised child, and the child's family, must be respectful of the child, of the child's family, and of the family's culture. Any experience of marginalisation is, in itself, traumatic. Respecting a child means recognising and understanding that even emotions that seem annoying or out of proportion to us are real and valid. We need to show empathy, listen actively — and we may well need to regulate our own stress responses, too.

Parent-Child Mother Goose programs aim always to be respectful of the many cultural backgrounds of the families who attend our programs. When facilitators know a song or rhyme in a family’s first language, we will quietly demonstrate to them that we know it and ask them if we can sing it in the whole group. We also welcome the opportunity to learn new rhymes, songs and stories that they may wish to share with us. Some Parent-Child Mother Goose programs cater specifically for particular cultural and/or language groups. We know of programs that have run successfully in Persian and Mandarin, and also of programs that have run specifically for African refugees and for Vietnamese families. When it comes to telling stories in Parent-Child Mother Goose sessions, facilitators are encouraged through their training to consider choosing stories that have originated in a wide range of different cultures, and respectfully explain the origins of a story before they tell it. When the question arises as to whether or not it could be appropriate for a facilitator to tell a particular aboriginal story to a particular group, we always advise facilitators to seek the advice of their local aboriginal community elders or corporation. When working inclusively with children whose initial response to participating in a new Parent-Child Mother Goose group is behaviour that may seem "out of proportion" (more than likely to the embarrassment of the child's parent or caregiver) experienced facilitators will recognise that this is the child's response to an unfamiliar situation, will reassure the parent or caregiver that they are, indeed, welcome, and that this is not the first time such things have happened, and will encourage both parent and child to "dip their toe in the water" slowly, as it were, in small steps. Many children who have learned to enjoy their Parent-Child Mother Goose over time are unsettled and upset at first. At such moments, we often might introduce a lullaby and ask families to stand and gently dance with their children. If the upset is so great and prolonged that a parent wishes to leave, it's good practice if one of the facilitators quietly walks out with the family, reassures as far as possible, and asks permission to phone later. Sometimes we have found it helpful if that family can arrive early, before sessions begin, so the child can enter the room on their own terms and have time to settle. Conclusion

It does appear to us that Dr Perry's model of developmental trauma, and trauma reparation, is not only highly insightful and valuable in itself, but also illuminates, with remarkable clarity, how and why the Parent-Child Mother Goose program "works" at so many different levels. Through his role as Founder and Senior Fellow of the Child Trauma Academy, Dr Perry today is now driving an effort to train a significant body of professionals around the world in NMT with a view to helping traumatised children who have reached school age recover from the profound neurological insult their brains have suffered in the earliest year or so of their lives. At the same time, Dr Perry recognises the great importance of programs and practices (such as Parent-Child Mother Goose, we would suggest) that "target the first years to provide consistent predictable nurturing supports for mothers and for the families" (Early Years Scotland, 2017). We could not agree more. Indeed, we'd like to say thank you, Dr Perry, for your work and for your passionate advocacy in this cause. We're greatly impressed!

Peter Dann February 2022 Further reading

The ChildTrauma Academy Library is a set of free resources for parents, caregivers, educators and professionals. https://www.childtrauma.org/cta-library Beacon House Resources are "freely available resources so that knowledge about the repair of trauma and adversity is in the hands of those who need it." ttps://beaconhouse.org.uk/resources/ References

Carrington, K., Morley, C., Warren, S., Ryan, V., Ball, M., Clarke, J. & Vitis, L. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Australian domestic and family violence services and their clients. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 56(4), 539-558. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.2825 Chicago Ideas. (2015, 2 May). The Body's Most Fascinating Organ: The Brain [Video] YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1MsLtnv3nCE Douglas, A. (2021). Meeting Children Where They Are: The Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics. Adoption Advocate, 160, 1-10. Early Years Scotland. (2017, November 16). Dr Bruce Perry - Early Brain Development: Reducing the Effects of Trauma [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hp6fZrzgiHg Ludy-Dobson, C. & Perry, B. (2010). The Role of Healthy Relational Interactions in Buffering the Impact of Childhood Trauma. In Gil, E. (Ed.) with Terr, L., Working with Children to Heal Interpersonal Trauma: The Power of Play (pp. 26-43). The Guilford Press. Lyons, S., Whyte, K., Stephens, R. & Townsend, H. (2020). Developmental Trauma Close Up. Beacon House Therapeutic Services and Trauma Team. Version 2. https://www.beaconhouse.org.uk/useful-resources MacKinnon, L. (2012) The Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics: An interview with Bruce Perry. The Australian & New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 33(3) 210-218 https://doi.org/10.1017/aft.2012.26 Perry, B., Pollard, R., Blakley, T., Baker, W. & Vigilante, D (1995). Childhood Trauma, the Neurobiology of Adaptation, and "Use-dependent" Development of the Brain: How "States" become "Traits". Infant Mental Health Journal, 16(4), 271-291. Perry, B., The ChildTrauma Academy (2013a) 1: The Human Brain [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uOsgDkeH52o Perry, B., The ChildTrauma Academy (2013b) 2: Sensitization and Tolerance [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qv8dRfgZXV4 Perry, B., The ChildTrauma Academy (2013c) 3: Threat Response Patterns [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sr-OXkk3i8E Rhythmic Mind. (2018, June 7). Dr. Bruce Perry Interview [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a9NtmRj0tm8 |